Day_06: Chaos in Motion#

The double pendulum solution and mini benchmarking#

Today, I wanted to build upon my recent successes with Julia and build my own double pendulum gif. I love these examples e.g. wikipedia, @DatSwingyBoi.

I built up the solution in 3 steps:

build a differential equation

time solutions using different solver methods

compile lots of solutions into one animated gif

using Plots, DifferentialEquations, LaTeXStrings

[ Info: Precompiling Plots [91a5bcdd-55d7-5caf-9e0b-520d859cae80] (cache misses: wrong dep version loaded (2))

Failed to precompile Plots [91a5bcdd-55d7-5caf-9e0b-520d859cae80] to "/home/ryan/.julia/compiled/v1.11/Plots/jl_ct38nG".

Stacktrace:

[1] error(s::String)

@ Base ./error.jl:35

[2] compilecache(pkg::Base.PkgId, path::String, internal_stderr::IO, internal_stdout::IO, keep_loaded_modules::Bool; flags::Cmd, cacheflags::Base.CacheFlags, reasons::Dict{String, Int64}, isext::Bool)

@ Base ./loading.jl:3085

[3] (::Base.var"#1082#1083"{Base.PkgId})()

@ Base ./loading.jl:2492

[4] mkpidlock(f::Base.var"#1082#1083"{Base.PkgId}, at::String, pid::Int32; kwopts::@Kwargs{stale_age::Int64, wait::Bool})

@ FileWatching.Pidfile ~/projects/julia/usr/share/julia/stdlib/v1.11/FileWatching/src/pidfile.jl:95

[5] #mkpidlock#6

@ ~/projects/julia/usr/share/julia/stdlib/v1.11/FileWatching/src/pidfile.jl:90 [inlined]

[6] trymkpidlock(::Function, ::Vararg{Any}; kwargs::@Kwargs{stale_age::Int64})

@ FileWatching.Pidfile ~/projects/julia/usr/share/julia/stdlib/v1.11/FileWatching/src/pidfile.jl:116

[7] #invokelatest#2

@ ./essentials.jl:1057 [inlined]

[8] invokelatest

@ ./essentials.jl:1052 [inlined]

[9] maybe_cachefile_lock(f::Base.var"#1082#1083"{Base.PkgId}, pkg::Base.PkgId, srcpath::String; stale_age::Int64)

@ Base ./loading.jl:3609

[10] maybe_cachefile_lock

@ ./loading.jl:3606 [inlined]

[11] _require(pkg::Base.PkgId, env::String)

@ Base ./loading.jl:2488

[12] __require_prelocked(uuidkey::Base.PkgId, env::String)

@ Base ./loading.jl:2315

[13] #invoke_in_world#3

@ ./essentials.jl:1089 [inlined]

[14] invoke_in_world

@ ./essentials.jl:1086 [inlined]

[15] _require_prelocked(uuidkey::Base.PkgId, env::String)

@ Base ./loading.jl:2302

[16] macro expansion

@ ./loading.jl:2241 [inlined]

[17] macro expansion

@ ./lock.jl:273 [inlined]

[18] __require(into::Module, mod::Symbol)

@ Base ./loading.jl:2198

[19] #invoke_in_world#3

@ ./essentials.jl:1089 [inlined]

[20] invoke_in_world

@ ./essentials.jl:1086 [inlined]

[21] require(into::Module, mod::Symbol)

@ Base ./loading.jl:2191

Build the double pendulum differential equations#

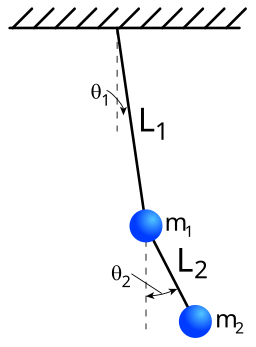

The double pendulum is a great example of the butterfly effect. Two masses are attached to each other by rigid connections e.g. $L_1$ and $L_2$ are constant. They have to rotate around each other in a circle, but the results are almost never the same. Two double pendulums with initial conditions that are nearly identical end up creating two diverging paths.

I used the Lagrangian approach to build the differential equations,

$T = \frac{1}{2}m_1v_1^2 + \frac{1}{2}m_2v_2^2$

$V = m_1gL_1\cos\theta_1 + m_2g\left(L_1\cos\theta_1+L_2\cos\theta_2\right)$

$L = T - V$

$\frac{d}{dt}\left(\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{\theta}_i}\right) - \frac{\partial L}{\partial \theta_i} = 0$

where

$v_1^2 = L_1^2\dot{\theta}_1^2$

$v_2^2 = L_1^2\dot{\theta}_1^2 + L_2^2\dot{\theta}_2^2 + L_1L_2\dot{\theta}_1\dot{\theta}_2\cos\left(\theta_1 -\theta_2\right)$

It took a little patience and book-keeping, but the final equations are two, coupled ordinary differential equations

$\left(m_1L_1^2 + m_2L_1^2\right)\ddot{\theta}_1 + m_2L_1L_2\cos\left(\theta_1 - \theta_2\right)\ddot{\theta}_2 +m_2L_1L_2\dot{\theta}_2^2\sin\left(\theta_1 - \theta_2) + (m_1gL_1 + m_2 g L_1\right)\sin\theta_1$

$m_2L_1L_2\cos\left(\theta_1 - \theta_2\right)\ddot{\theta}_1 + m_2L_2\ddot{\theta}_2 - m_2L_1L_2\dot{\theta}_1^2\sin\left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right) +m_2gL_2\sin\theta_2$

I created the function, doublependulum, to calculate the change in

state, du

$=\dot{\theta}_1,~\dot{\theta}_2,~\ddot{\theta}_1,~and~\ddot{\theta}_2$

given

the state,

u$=\theta_1,~\theta_2,~\dot{\theta}_1,~and~\dot{\theta}_2$.the parameters,

param$=L_1,~L_2,~m_1,~and~m_2$the time,

there the equations are not directly related to time though

I collected the “mass” terms–anything multiplied by

$\ddot{\theta}_{1/2}$–and created the $2\times2$ matrix, M. I put everything else in the

2-element vector, rhs. Now, the acceleration is calculated with the \ operation.

This little, \ operator was one of my favorite parts of MATLAB. It felt so intuitive and easy-to-use.

M*du = rhs

# so

du = M\rhs

function doublependulum(u, params, t)

g = 9.81

du = zeros(length(u))

l1 = params[1]

l2 = params[2]

m1 = params[3]

m2 = params[4]

du[1] = u[3]

du[2] = u[4]

M = [l1*(m1+m2) m2*l1*l2*cos(u[1] - u[2]);

m2*l1*l2*cos(u[1] - u[2]) m2*l2]

rhs = [-m2*l2*u[4]^2*sin(u[1] - u[2]) - (m1+m2)*g*sin(u[1]);

m2*l1*l2*u[3]^2*sin(u[1] - u[2]) - m2*g*l2*sin(u[2])]

du[3:4] = M\rhs

return du

end

doublependulum (generic function with 1 method)

Make a test run to check the differential equations#

With the differential equations defined inside doublependulum, I built two ODEProblems and plotted $\theta_2$ to look for divergence. If the equations are defined correctly, I should see that the angles are very close for short times, but diverge the longer the time span.

I chose ODEProblem parameters as such

timespan 0-20 seconds,

tspan = (0, 20)$L_1 = L_2 = 1~m,~and~m_1 = m_2 = 0.1~kg$,

p = [1, 1, 0.1, 0.1]initial condition: release from rest at $\theta_1 = 114.59^o~and~\theta_2 = 114.59^o~and~114.65^o$,

[2, 2, 0, 0]and[2, 2.001, 0, 0]_a difference of $\approx 3~min~or~\frac{3}{60}~degrees$

Plots.theme(:cooper)

tspan = (0, 20);

p = [1, 1, 0.1, 0.1];

prob1 = ODEProblem(doublependulum, [2, 2, 0, 0], tspan, p)

sol1 = solve(prob1)

prob2 = ODEProblem(doublependulum, [2, 2.001, 0, 0], tspan, p)

sol2 = solve(prob2)

X = zeros()

t = range(0, tspan[2], 500)

a21 = [sol1(ti)[2] for ti in t]

a22 = [sol2(ti)[2] for ti in t]

plot(t, a21, label = L"$\theta_2(0) = 2.000$")

plot!(t, a22, label = L"$\theta_2(0) = 2.001$",

xlabel = "time (s)",

ylabel = L"$\theta_2$")

Around 6-7 seconds into the prediction, the two solutions diverge. Success.

Time the solutions to the double pendulum#

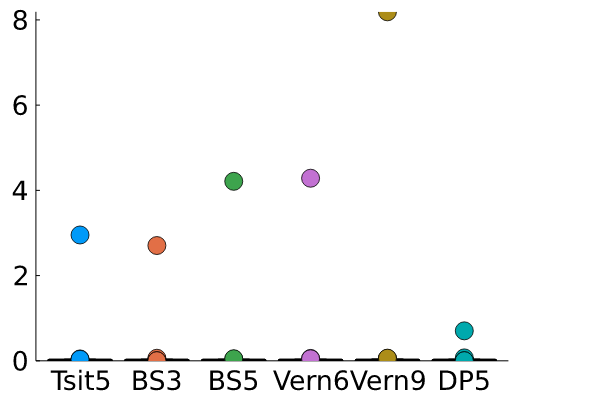

Since, I want to compare lots of solutions, I wanted to try out the @timed function and compare a few different integration methods.

Note: This is not a full “benchmarking” analysis. I am not tweaking parameters to compare apples-to-apples here, I’m just blindly running and choosing the fastest result. Your mileage will vary. The

BenchmarkToolslook much more capable of building insights into these results, but here I’m starting simple.

I looked at the Three Body Work-Precision methods and picked out some possible ODE integration methods,

Tsit5(): Tsitouras 5/4 Runge-Kutta method. (free 4th order interpolant).BS3(): Bogacki-Shampine 3/2 methodBS5(): Bogacki-Shampine 5/4 methodVern6(): Verner’s “Most Efficient” 6/5 Runge-Kutta method. (lazy 6th order interpolant).Vern9(): Verner’s “Most Efficient” 9/8 Runge-Kutta method. (lazy 9th order interpolant)DP5(): Dormand-Prince’s 5/4 Runge-Kutta method. (free 4th order interpolant).

Note: for more integration options and explanations, check the DifferentialEquations ODE Solvers page.

I set up the ODEProblem as the doublependulum with $\theta_1 = \theta_2 = 2~rad$ starting from rest i.e. [2, 2, 0, 0]. The pendulum lengths and masses are $L_1 = L_2 = 1~m$ and $m_1 = m_2 = 0.1~kg$.

tspan = (0, 20);

p = [1, 1, 0.1, 0.1];

prob = ODEProblem(doublependulum, [2, 2, 0, 0], tspan, p)

ODEProblem with uType Vector{Int64} and tType Int64. In-place: false

timespan: (0, 20)

u0: 4-element Vector{Int64}:

2

2

0

0

I made a list of methods to try in methods and then compiled 100 trials, Nruns = 100. The statistics for each timed run was saved inside stats using two list comprehensions,

for each run

range(1, Nruns)I timed the givensolutions_method(method)repeat for each

methodcontained inmethods

function solution_method(method)

sol = solve(prob, method)

# print(sol[end][2])

end

# @time solution_method()

Nruns = 100

methods = [Tsit5(), BS3(), BS5(), Vern6(), Vern9(), DP5()]

stats = [[@timed solution_method(method) for i in range(1, Nruns)] for method in methods];

I compared the times and memory useage by printing out the mean and standard deviations across the 100 evaluations,

for (i, m) in enumerate(methods)

avgT = mean([stats[i][j].time for j in range(1, Nruns)])

sigT = std([stats[i][j].time for j in range(1, Nruns)])

avgB = mean([stats[i][j].bytes for j in range(1, Nruns)])

sigB = std([stats[i][j].bytes for j in range(1, Nruns)])

print(split(string(m), "(")[1],"| avg time = ", avgT, "+/-", sigT,"\n")

print(split(string(m), "(")[1],"| avg size = ", avgB, "+/-", sigB,"\n")

end

out:

Tsit5| avg time = 0.03184966183000001+/-0.295094360432862

Tsit5| avg size = 9.97361955e6+/-7.383699550000001e7

BS3| avg time = 0.029934179349999993+/-0.2703186488655862

BS3| avg size = 1.017238704e7+/-7.216387040000002e7

BS5| avg time = 0.044493667269999995+/-0.4209777166311047

BS5| avg size = 1.239656072e7+/-1.0026528719999999e8

Vern6| avg time = 0.04626529728999999+/-0.4281718618312509

Vern6| avg size = 1.410242284e7+/-1.0272486840000002e8

Vern9| avg time = 0.08686764361999998+/-0.8185455220658197

Vern9| avg size = 1.740738218e7+/-1.1960118179999997e8

DP5| avg time = 0.009356491289999998+/-0.07042112542403473

DP5| avg size = 3.40718885e6+/-7.580208500000002e6

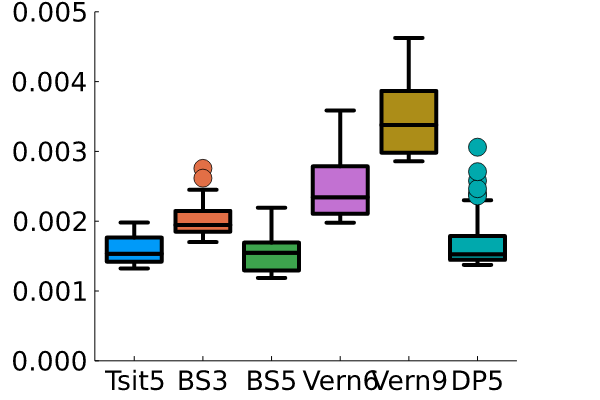

These results weren’t very pretty, but they do contain a lot of information. Next, I use a boxplot of the results.

using StatsPlots

boxplot([[stats[i][j].time for j in range(1, Nruns)] for i in range(1, length(methods)) ],

label = "", ylim = (0, :auto))#[split(string(m), "(")[1] for m in methods])

plot!(xticks = (range(1, 6), [split(string(m), "(")[1] for m in methods]))

The outliers swamp the average and standard deviations of these runs, so here I set the ylim to 5 ms.

boxplot([[stats[i][j].time for j in range(1, Nruns)] for i in range(1, length(methods)) ],

label = "", ylim = (0, 0.005))#[split(string(m), "(")[1] for m in methods])

plot!(xticks = (range(1, 6), [split(string(m), "(")[1] for m in methods]))

Now, I can see that the two fastest methods are Tsit5() and DP5(). There was no significant difference between these two methods. I’m sure there are methods to get even better results, but the methods blazingly fast and efficient for this little 2DOF nonlinear problem.

Compile lots of solutions into one gif#

Finally, I have

physics of the doublependulum defined in

doublependulumtiming results to choose

DP5()as my integration routine

Now, I want to save my results in a useable format so I can plot and animate the chaos effect in multiple double pendulums with slightly varying initial conditions. I use an array-based organization of my results:

given the three coordinates describing the hinge locations (0, 0), (X_1, Y_1), and (X_2, Y_2)

the number of timesteps,

timesteps = 500the number of pendulums,

Npendulums = 100

I create two 3D arrays with dimension lengths that match the number of coordinates, timesteps, and number of pendulums:

X = zeros(3, timesteps, Npendulums)Y = zeros(3, timesteps, Npendulums)

So, if I want to plot the position of the 10th pendulum in the first timestep, I can use the plot command,

plot(X[:, 1, 10], Y[:, 1, 10])

or I could plot the path taken by the second hinge, which should be a semicircle.

plot(X[2, :, 10], Y[2, :, 10])

Each of the dimensions for X and Y are <hinge #>, <timestep>, <pendulum #>.

tspan = (0, 20);

p = [1, 1, 0.1, 0.1];

Npendulums = 100

timesteps = 500

dtheta2 = range(0, 0.001, Npendulums);

t = range(0, tspan[2], timesteps);

X = zeros(3, timesteps, Npendulums);

Y = zeros(3, timesteps, Npendulums);

Here, I loop through and store the solutions into X and Y.

theta2_0is the initial angle for $\theta_2$. It varies from 2-2.001 radiansprobdefines the differential equation, including its initia; conditions, timespan and parameterssol_dp5is the integration result from theDP5()methodsolinterpolates the results to the same timesteps,t = range(0, 20, timesteps)x1, y1, x2, y2are the hinge positions, $[L_1\sin\theta_1,~-L_1\cos\theta_1]$ and $[L_1\sin\theta_1+L_2\sin\theta_2,~-L_1\cos\theta_1-L_2\cos\theta_2]$

for pend_i in range(1, Npendulums)

theta2_0 = 2 + dtheta2[pend_i]

prob = ODEProblem(doublependulum, [2, theta2_0, 0, 0], tspan, p)

sol_dp5 = solve(prob, DP5())

sol = sol_dp5(t)

x1 = [p[1]*sin(sol.u[i][1]) for i in range(1, timesteps)]

x2 = [p[1]*sin(sol.u[i][1]) + p[2]*sin(sol.u[i][2]) for i in range(1, timesteps)]

y1 = [-p[1]*cos(sol.u[i][1]) for i in range(1, timesteps)]

y2 = [-p[1]*cos(sol.u[i][1]) - p[2]*cos(sol.u[i][2]) for i in range(1, timesteps)]

X[2, :, pend_i] = x1

X[3, :, pend_i] = x2

Y[2, :, pend_i] = y1

Y[3, :, pend_i] = y2

end

I want to color code each pendulum and path. Here, I use the ColorSchemes to set the colors for the pendulums. Using 10 pendulums, I would have these 10 colors from the rainbow scheme.

import ColorSchemes.rainbow

get(rainbow, range(0, 1, length = 10))

Plot the gif frames#

I took some time to build a nice dynamic and customizable plot. There are a lot of lines to get it to look the way I wanted. Walking through the steps of the @gif loop,

the

for-loop increments thetendvalue from the second timestep through the final timestep,timesteps = 500initialize the plot with

a title

"Chaos in motion"equal axes,

xlim = ylimandaspect_ratio = :equalremove axes

axis = nothingandshowaxis = false

show the last 100-steps in the path of the pendulum if the current time is greater than 100 steps

if tend < pathlength+1whentendis less than thepathlength = 100just plot all of the points, tstart = 1elsewhen tend is more thanpathlength = 100plot the last 100 values,tstart = tend - 100

Set the color of the current pendulum:

pend_color = get(rainbow, (pend_i-1)/(Npendulums - 1))scale goes 0-1 forgetPlot each pendulum at the current time and its path

for pend_i in range(1, Npendulums)plot the path of the end of the pendulums:

plot!(X[3, tstart:tend, pend_i], Y[3, tstart:tend, pend_i)Fade out old path values by setting the opacity to vary from 1=current time, to 0=100 timesteps backward:

seriesalpha = range(0, stop=1, length = 1+tend-tstart))plot the current pendulum shape:

plot!(X[1:3, tend, pend_i], Y[1:3, tend, pend_i])add markers for the pendulums:

markershape = :circle, markercolor = pend_color, markeralpha = 0.5

Npendulums = 10

pathlength = 100

@gif for tend in range(2, timesteps)

p = plot(title = "Chaos in motion",

xlim = (-2, 2),

ylim = (-2, 2),

aspect_ratio = :equal,

axis = nothing,

showaxis = false)

if tend < pathlength+1

tstart = 1

else

tstart = tend - pathlength

end

for pend_i in range(1, Npendulums)

pend_color = get(rainbow, (pend_i-1)/(Npendulums-1))

plot!(X[3, tstart:tend, pend_i], Y[3, tstart:tend, pend_i],

label ="",

linecolor = pend_color,

seriesalpha = range(0, stop=1, length = 1+tend-tstart))

plot!(X[1:3, tend, pend_i], Y[1:3, tend, pend_i], markershape = :circle,

label = "",

linecolor = pend_color,

linealpha = 0.5,

markercolor = pend_color,

markeralpha = 0.5)

end

end

┌ Info: Saved animation to

│ fn = /home/ryan/Documents/Career_docs/cooperrc-gh-pages/Julia-learning/tmp.gif

└ @ Plots /home/ryan/.julia/packages/Plots/D9pfj/src/animation.jl:114